“Streets with trees come to hold a cherished place in the hearts and minds of those living with them…recollections of growth from seedling to maturity, of gracious light and shade, brilliant young green of spring-time, dignified shade in the heat of the day“.

W. B. Bailey-Tart

Every spring, as October fades and the heat of the coming summer begins to crackle in the air, something magical unfurls across parts of Australia. Streets are flush with colour. Mauve canopies stretch overhead. Footpaths are transformed into purple carpets. It’s Jacaranda season.

To the uninitiated, these luminous trees are as Australian as meat pies or magpies. But Jacaranda mimosifolia, the variety most Australians associate with the name, is not native to our continent. It comes from the sunburnt highlands of the piedmont forests of the Andes in northwestern Argentina and southern Bolivia. It is adapted to harsh, dry conditions in elevations up to 2,600 metres. Its resilience to aridity and frost and a tolerance for poor soils made it a prime candidate for acclimatisation beyond its native range.

Native American in name, “jacaranda” deriving from the Tupi word yacaranda, meaning “hard branch or core”, the tree belongs to the Bignoniaceae family. Although the genus contains nearly fifty species, it is mimosifolia the “blue jacaranda” that dominates horticulture, prized for its lush, violet-purple blooms and graceful form.

These trees, born of dry forests and lean soils, are ideally suited to our parched landscapes. Yet they have truly found their second home and something approaching stardom here, particularly in places like Grafton in northern New South Wales.

A tree for the empire

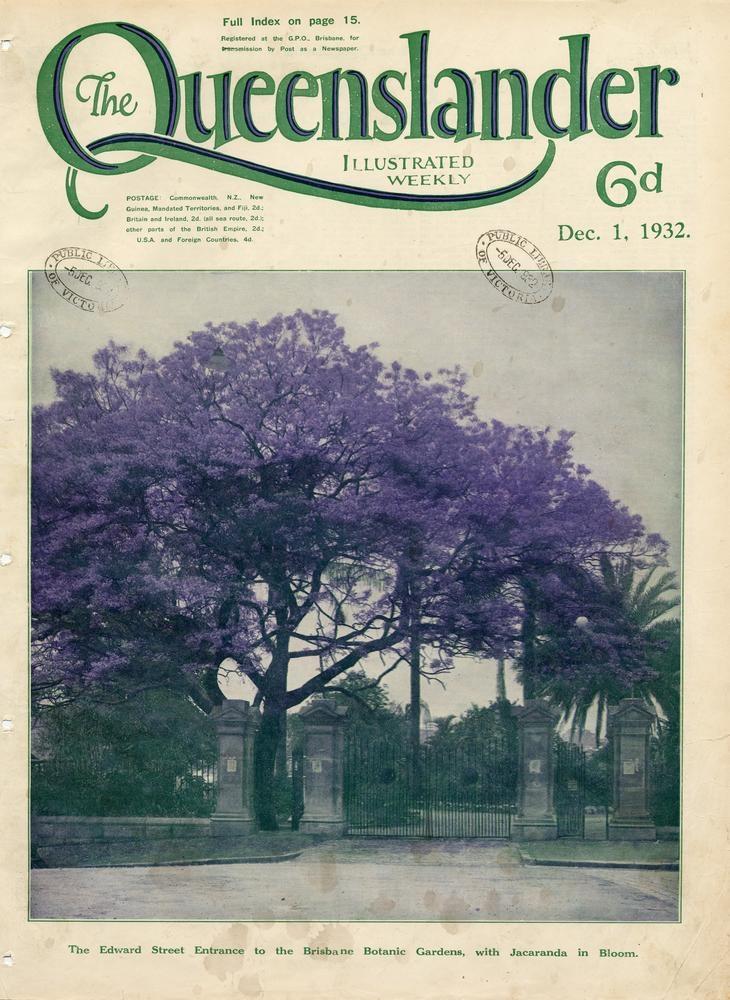

Europe’s 19th-century thirst for exotic species brought jacaranda saplings to distant lands, fuelled by a colonial enthusiasm for the unusual and ornamental. In Australia, it made its debut relatively early. It was first recorded in Sydney’s Botanic Gardens in the 1850s, with a notable tree planted around 1850–1860 that is now over 175 years old. Brisbane followed in 1864, thanks to Walter Hill, the curator of the Botanic Gardens, who secured seeds from returning South American sea captains.

This was the age of acclimatisation societies and botanic gardens, when Europe’s expanding empire brought back plant specimens like trophies, planting them across foreign soils in acts of civilising ambition. To grow a jacaranda in colonial Australia was to drape the land in a European aesthetic, softened by tropical extravagance. It was civic pride with a lilac flourish. The jacaranda’s vibrant blooms dramatically coloured the landscape, suggesting cultivation and control over the wildness of suburbia.

In Grafton, the story took hold with great intensity. The first plantings commenced in the 1870s, when seed merchant Henry A. Volkers was commissioned by the Grafton Council to source and plant jacaranda trees. Over the subsequent decade, hundreds of these South American imports lined the city’s streets, transforming it into a lavender-hued townscape.

By the early 20th century, the city’s vision had narrowed its focus to planting only jacarandas. From 1900 to the 1920s, the local council committed to their mauve master plan, lining street after street with Jacaranda mimosifolia until the town transformed into a blooming spectacle, establishing a singular seasonal identity.

As Elizabeth Oriel wrote:

“Planting jacarandas as street trees in Grafton has been an effort to civilise the city, and it is part of a larger movement to establish an Australian urban aesthetic“.

By 1935, the phenomenon was established. That year, the Jacaranda Festival, Australia’s oldest floral celebration, was born and arguably Australia’s first traditional community festival. The organiser was E. H. “Jacaranda Bill” Chataway, who made the festival his first central civic mission when elected to the council in 1934.

It began as a modest civic event based on folk dancing, and has developed into a cherished, week-long tradition that attracts tens of thousands of visitors. At the height of the festival, Grafton transforms into a vibrant postcard, overflowing with colour, music, art, parades, and the crowning of the Jacaranda Queen. Traditionally, the queens of the two previous years act as the maids of honour. Mavis McClymott eloquently summarised the occasion:

” A fragrant, delicate crown of jacaranda blossom has rested upon the silken tresses of blondes, brunettes and titians. Over the years the spirit of the festival has been personified by a Jacaranda Queen“.

What was once an act of imperial landscaping has become a deeply local, nearly sacred tradition.

The bloom and the panic

For all their glory, jacarandas are capricious. They drop their leaves in late winter, then suddenly and spectacularly bloom. The flowers emerge directly from bare wood, lending the trees their ethereal, floating appearance. The bloom typically begins early to mid-October and reaches full splendour by late October. By early November, the petals start their gentle fall, blanketing roads, footpaths, and parks in purple confetti.

It’s this short-lived brilliance that makes them so enchanting. Like cherry blossoms in Japan or tulips in the Netherlands, jacarandas are beautiful partly because they don’t last. Their season is fleeting, a fact that amplifies their emotional appeal.

As a former student at the University of Queensland, I know this all too well. The jacaranda signals the onset of exams, giving rise to a local phenomenon known as purple panic. The old joke goes that it’s already too late if you haven’t started studying before the jacarandas bloom.

But there’s nothing panicked about the trees themselves. They bloom with complete indifference to human schedules. They have their rhythm, a kind of “vegetal wisdom”. Wait for the dry. Drop the leaves. Save water. Then bloom like it’s the end of the world.

Trees of memory and meaning

Despite their foreign origins, jacarandas have entrenched themselves in the Australian psyche. They appear in poems, paintings, postcards, and pop culture. In Grafton, people time their weddings to the bloom. Children remember walking to school beneath purple tunnels. Old-timers recall collecting the tough seed pods, those flat, round discs like nature’s coins, to make Christmas decorations. Even their litter is beloved, and as petal falls, it transforms the everyday into a cinematic display.

Jacarandas are also a masterclass in placemaking. Their colour casts a spell on cities. A purple street is suddenly more photogenic, and a humble park becomes a destination. In Grafton, the trees have helped define the town’s visual identity and cultural rhythm.

But jacarandas also remind us of the contradictions in our landscape. They are celebrated here, even while declining in their native range. The IUCN lists Jacaranda mimosifolia as vulnerable in the wild, whose future is precarious.

And in Australia, where non-native species are often viewed with suspicion, the jacaranda gets a pass, possibly because it behaves itself—it rarely invades bushland or competes with native flora. Instead, it sticks to its assigned role as a civilised, obedient tree in tidy streetscapes.

A tree worth celebrating

Of course, not everyone is enchanted. Some urban managers worry about slippery footpaths, clogged gutters, or the relentless sweep-up required each November. But few would dare suggest removing them. Doing so in Grafton might be akin to heresy. The jacaranda is not just a tree but part of the town’s soul.

So, if you ever find yourself in northern New South Wales around late October, treat yourself and drive to Grafton. Stroll beneath those towering canopies. Breathe in the delicate fragrance. Watch the petals fall like soft rain. And as you crunch through the mauve confetti on the footpath, think of the remarkable journey these trees have made from the dry hills of South America to the heart of a blossoming Australian tradition.

While Jacaranda mimosifolia began its life far from the Australian suburbs, it now blesses the Aussie countryside with a purple reign each October, an unforgettable reign for a few brief weeks each year.